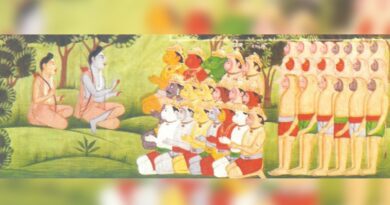

A tale of many Ramkathas

The story of Rama (Ramakatha) has been described by many scholars in many languages. Geographies and is set in varied time periods. Gulshan Kumar Rawat talks of some of those renditions

The number of Ramayanas (essentially stories of Rama) and the range of their influence in South and Southeast Asia is astonishing. There is a long list of languages in which Rama’s story is to found Balinese, Bengali, Kannada, Sanskrit, Telugu, Santhali and Thai among others.

Few texts actually bear the title Ramayana; they are given titles like Iramavataram (the incamation of Rama). Ramacaritmanas (the lake of the acts of Rama), Ramakein (the stories of Rama) and so on. Their relation to Rama’s story as told by Valmiki (the most famous one, incidentally also the one that ABVP swears by) also vary.

Kampan wrote Iramavataram in Tamil in poetry form; in the 18th century, the story of Rama was written in Thai and was called Ramkien. It borrows heavily from the Tamil epic. Names of many characters in the Thai work are not Sanskrit names, but essentially Tamil names.

Even Tulsidas’ Ramacaritmanas and the Malaysian Hikayatseriram share many things with Kampan’s rendition of the story of Rama.

Through the centuries some languages have even hosted more than one telling of the Rama story. For instance, Sanskrit alone contains some 25 or more tellings belonging to various narrative genres (epics, kavyas or puranas). If we add plays, dance, drama and other art forms, the number of Ramayanas‘ grows even larger.

The South Indian folk Ramayana, sung by an untouchable bard, opens with Ravana (here called Ravula) and his queen Mandodari. They are spoken of as unhappy and childless. In the hope of getting a baby Ravana goes to forest and performs self-mortification. He becomes pregnant as a result of consuming the fruit given by Lord Shiva (who had appeared as a sage) instead of sharing it with his wife as had been directed. To avoid a curse, he puts the baby in a box and leaves her in Janaka’s field.

In accordance, the word Sita means ‘he sneazed’ in Kannada. Likewise in one of the Sanskrit versions, the baby is named Sita because the king Janaka finds her in a furrow (sita). These tellings depict Sita as Ravana’s daughter.

Such motif of Sita being Ravanas daughter is not unknown elsewhere. It also occurs in a tradition of Jain stories (in the Vasudevahimdi) and in the folk tradition of Kannada and Telugu, as well as in several Southeast Asian renditions of Ramayana.

In some versions, Ravana molests a young woman in his lusty youth. The woman vows vengeance and is reborn as his daughter to destroy him. In this way, the oral tradition of rendering the tale of Rama partakes yet another set of themes unknown in Valmiki’s Ramayana.

The Jain Ramayana of Vimalasuri called Paumacariya opens with Ravana. He is shown one of the 63 leaders or salakapurusas of the Jain tradition. He is noble, learned, earns all his magical powers and weapons through austerities and is a devotee of Jain masters.

One more motif works in the Jain way of thinking: a pair of antagonists, Vasudeva and Prativasudeva, a hero and an anti-hero, is destined to fight in every lifetime. Vasudeva inevitably kills his counterpart in every encounter. Lakshman and Ravana are the eighth incarnation of this pair. Lakshman, a Vasudeva, slays Ravana with his magical weapons. Note that in this Jain rendition, Rama does not kill Ravana as he does in the Hindu Ramayana of Valamiki.

The Thai Ramayana is called Ramakidi portrays Hanuman as a small monkey who does not mind looking into the bedrooms of Lanka and does not consider seeing another man’s sleeping wife immoral, unlike Valmiki or Kampan’s Hanuman.

Ravana too is different here. The Ramakriti admires Ravana’s resourcefulness and learning. His abduction of Sita is seen as an act of love and is viewed with sympathy. Unlike Valmiki’s characters, Ramakriti’s characters are fallible; Human is a mixture of good and evil.

The fall of Ravana in Ramakriti makes one sad. It is not on occasion of unambiguous rejoicing, as it is in Valmiki’s Ramayana. To some extent, all later Ramayanas play on the knowledge of previous tellings; they are actually meta-Ramayanas.